I have been crucified with Christ; and it is no longer I who live, but Christ lives in me; and the life which I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave Himself up for me. (Galatians 2:20)

We can’t leave the discussion of fourteenth century Christian women mystics without talking about Dorothy of Montau. Truly, Dorothy identified with the crucified Christ all of her life. She knew that He loved her first and she returned the love.

It is interesting that the Christian women mystics of the Middle Ages lived in many areas of Europe – England (Julian of Norwich, Margery Kempe), France (Jeanne Guyon), Italy (Catherine of Siena, St. Clare of Assisi, Angela of Foligno), Spain (Teresa of Avila), Sweden (Bridget), Hungary (Elizabeth of Hungary), Holland (Hadewijch) and Germany (Hildegard, Mechthild of Magdeburg, Mechthild of Hackeborn, Gertrude the Great). Spread out far and wide these women shared the same message of love for the Savior. They all had the same Holy Spirit. Their lives influenced thousands of people. God was definitely at work in the lives of Christian Medieval women.

Many of these amazing women were “firsts” — Julian of Norwich has the honor of being the first published author in all of English literature. Catherine of Siena who was the first woman to be published in the Italian dialect. Birgitta of Sweden is also an acclaimed author of many books. Margery Kempe is the earliest known English autobiographer.

Dorothy of Montau was also a first – she was the first anchoress of the Prussian  frontier. (Today that area is called Poland.)

frontier. (Today that area is called Poland.)

Dorothy was born in Montau, Prussia on February 6, 1347 to a wealthy father and mother who were originally from Holland. She was the seventh of nine children, the youngest of five sisters. Even from a very early age Dorothy practiced a religious lifestyle of asceticism and extreme discipline.

At the age of sixteen Dorothy married a swordsmith named Albrecht of Danzig. He was over twice her age and was a very overbearing man. Dorothy began to have her spiritual visions almost immediately after her marriage. Albrecht had little patience with her spiritual experiences and began to abuse her.

Dorothy and Albrecht settled in Danzig and had nine children. Sadly, four of the children did not survive infancy. Four others died during the plague. Only one child, a daughter Gertrude, survived Dorothy. Gertrude joined the Benedictines at around age 10.

Dorothy continued to have visions and engage in the practice of extreme self-mortification. This distracted her to the point of neglecting her housework. Albrecht would beat her, but Dorothy thought of it as a part of her spiritual formation. According to her biographer, John of Marienwerder, Dorothy “would receive hard knocks while serving his [the husband’s] needs, for well-observed obedience is ‘more pleasing to God than sacrifices’. Thus when Albrecht punches her on the mouth for failing to prepare his fish supper she smiles at him with her fat lip. When she forgets to buy straw he beats her chest so hard that blood mingles with her saliva; she bears these blows joyfully.”

Today we would definitely call this domestic violence and Albrecht would be looking at square sunshine. However, during the Middle Ages penance and self-mortification were seen as being extremely spiritual. Recall that a group called the “flagellants” would go around at this time beating themselves on their backs until they bled. Why would they do this? The plague had claimed the lives of many thousands during the fourteenth century. Christians believed that God sent the plague to punish them. In line with the Roman Catholic teaching on penance, Christians believed that they could inflict punishment on themselves to pay for their sins and appease God. So, before we criticize Dorothy too much, let us remember the culture in which she found herself. In order to understand her actions we must understand her times and the teaching she received from her church.

When Dorothy was thirty-eight she and Albrecht went on a pilgrimage to Aachen. When returning home, she had what she considered her greatest visionary experience. Dorothy felt that her heart was physically ripped out and a new one put in its place. It’s hard to know exactly what happened to her; it’s hard to believe that it really physically happened. But this dream helps us to understand the depth to which the mystics’ experiences were felt by them; to them it was very real. Certainly there is at least a Biblical precedent for the changing of her heart. “I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit within you; I will take the heart of stone out of your flesh and give you a heart of flesh” (Ezekiel 36:26). The extent to which Dorothy felt this explains how emotional the mystics could be. We are not that way in our culture today; we tend to be more rational. The mystics always believed that there was a purpose to their suffering.

In 1387 Albrecht sold their possessions and they tried to move to Aachen. The journey by ship was full of hazards. The winter was extremely cold and Albrecht became ill. Because their attempt at moving did not work out they went back to Danzig.

Albrecht’s health began to worsen. Dorothy ministered to him unselfishly and compassionately even though Albrecht complained and continued to abuse her. They were so poor that Dorothy took to the streets to humbly beg for alms.

Albrecht actually got better and on a more loving impulse he told Dorothy that she could make a pilgrimage to Rome for the Jubilee year.

Jubilees were declared at momentous times during the history of the Church. In 1390 the Jubilee was going to be celebrated by the new pope, Boniface IX, who would open the door to the cathedral on Christmas Eve.

So in 1389, Dorothy traveled with a group of pilgrims to Rome for the 1390 Jubilee. By the time she returned home after the following Easter, her elderly husband was dead.

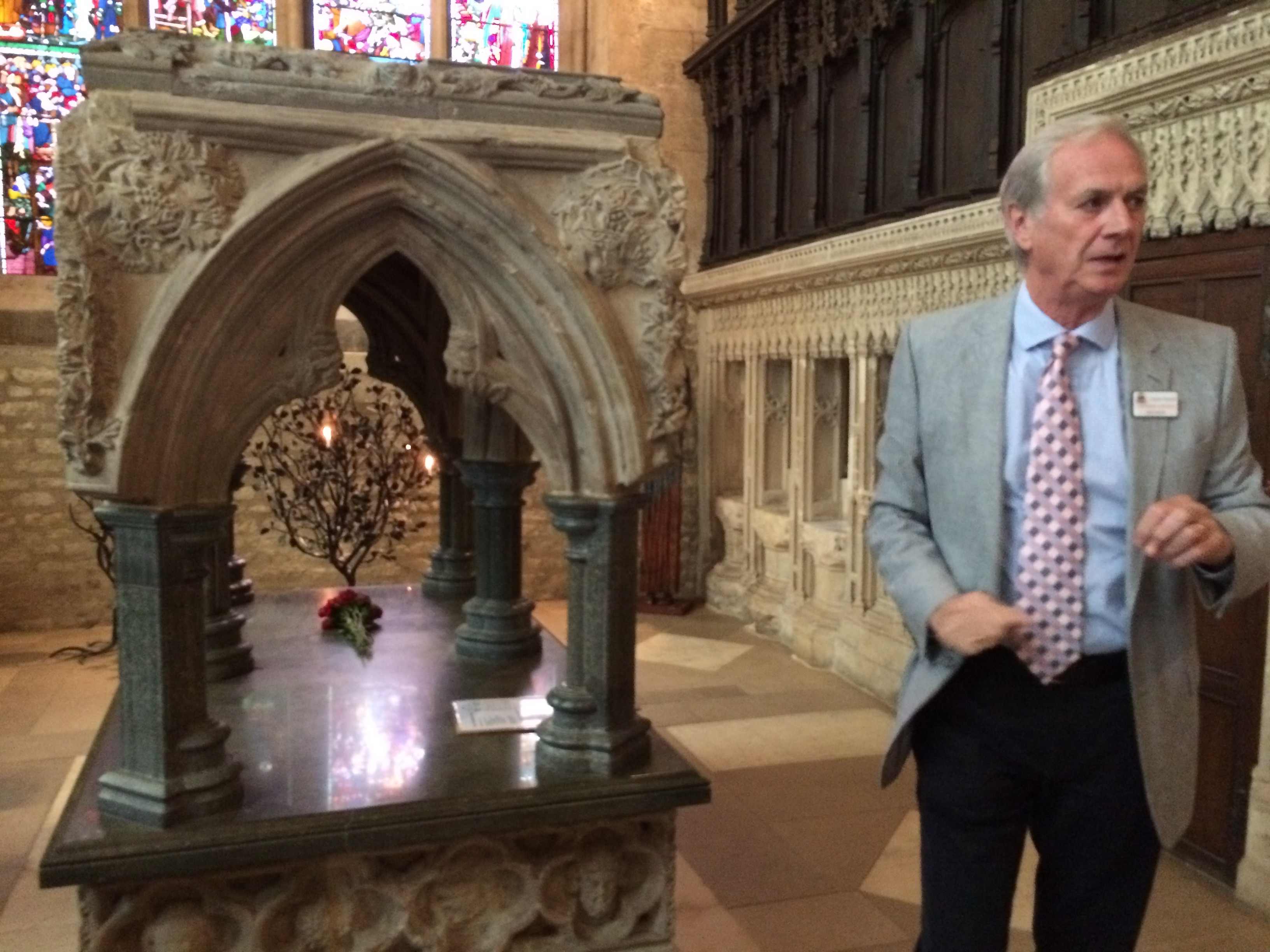

In 1393, with no one left for her to care for (Gertrude was at the convent in Kulm) Dorothy moved to Marienwerder. Here she became Prussia’s first anchoress. She was walled into a room attached to the Marienwerder cathedral. Her confessor, John of Marienwerder interrogated her intensively. He was convinced that she was truly a holy woman, declaring that her mystical experiences were of God not the devil.

In 1393, with no one left for her to care for (Gertrude was at the convent in Kulm) Dorothy moved to Marienwerder. Here she became Prussia’s first anchoress. She was walled into a room attached to the Marienwerder cathedral. Her confessor, John of Marienwerder interrogated her intensively. He was convinced that she was truly a holy woman, declaring that her mystical experiences were of God not the devil.

Dorothy spent the last year of her life in her cell. During that time many people visited her cell seeking spiritual advice. She died on June 25, 1394. On her deathbed she told one visitor that she was dying for the love of Jesus. At the age of 47, Dorothy went to be with her crucified and risen Savior.