Harriet Tubman- A Moses to her People

For the past several months we have been relating the stories of remarkable black women in America. We began with the stories of 18thand 19thcentury African-American women. Some were born as slaves and some were born free. All of these women were courageous examples of what can be done by a woman who does not let her circumstances dictate to her. These women rose above many hardships including poverty, illness, prejudice, internal conflicts, and the limitations of their times to follow their call from God and affect the lives of many other people for good. Why were they able to live in a realm above their circumstances? It is because they all received strength from God. They all answered the call in their lives to help others.

“I’ll meet you in de mornin’,

When you reach de promised land;

On de oder side of Jordan,

For I’m boun’ for de promised land.”

We recently watched “The Ten Commandments” a movie with Charlton Heston. It was made in the 1950’s when it was still ok to talk about the Bible in a movie in a positive way. The nearly four-hour movie told the story of Moses and the rescue of God’s people during the Exodus from Egypt.

We don’t know why God allowed His people to bear cruel slavery for four hundred years before sending a deliverer and rescuing them. We must not run the danger of accusing God for the evil that sinful men are doing. We do not know how even in this country we could have allowed the evil of slavery to continue for so long. We can express our sorrow but look back with thankfulness for the people that God raised up to work in their own way to end the oppression.

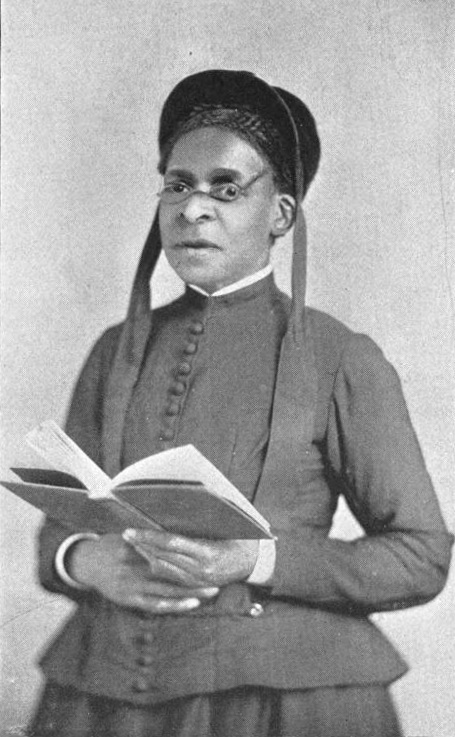

One woman who did just that was Harriet Tubman, the little lady who rescued three to four hundred slaves in the mid-nineteenth century, earning the title – a “Moses to her people”. Harriet would not blame God for any hard circumstances but instead she would acknowledge that her difficult upbringing prepared her for the tasks ahead of her when she followed her calling to rescue slaves.

Born Araminta Ross around 1820 to Benjamin Ross and Harriet Greene, both slaves, she later took her mother’s name, Harriet. She took her husband’s name when she married John Tubman.

Harriet was born in Maryland and had ten brothers and sisters. She was later able to rescue many family members and her parents, who retired in New York on property that Harriet purchased for them.

When Harriet was six years old she was sent to live with the James Cook family and learn the trade of weaving. Her mistress was cruel. James Cook sent her out to check muskrat traps, and so she had to wade in water. Already ill from measles she grew very sick and was eventually sent home.

When she was in her teens she worked as a field hand. While working for that farmer she received a wound to her head that would affect her for the rest of her life. The farm overseer was trying to punish a disobedient slave and threw a two-pound weight at him which fell short and hit Harriet, cracking her skull. It took her a long time to recover from this and for the rest of her life she was subject to sleeping spells. At times a sort of stupor would come over her even in the midst of a conversation and she would need to sleep. This would give the appearance of laziness or stupidity, but Harriet would show that she really had a fine mind and a courageous strength.

After this Harriet worked for John Stewart. She did many jobs usually given to men, such as cutting and hauling wood. Here she built up the incredible strength that would later allow her to do such things as carry grown men through the water to their safety.

Harriet married a free “colored” man named John Tubman around 1844. They had no children.

In 1849, she and some other slaves were to be sold. She determined not to be sold and so one night she just walked away. Eventually she arrived in Philadelphia where a white woman befriended her and she got a job. She saved her money and two years after her own escape from slavery she went south to rescue her husband. She found him living with another woman and unwilling to take her back. This did not stop her from her plan of rescuing other family members. She just moved on trusting in the Lord.

Between 1852 and 1857 she made many journeys to the south rescuing many people. It was during this time that people began to call her “Moses”, a name she retained for the rest of her life. She rescued so many people that a reward was put out for her capture.

Let’s don’t forget that a Fugitive Slave Law had been passed, making it a crime for people to help slaves escape. Harriet had to find ways to get the rescued slaves all the way to Canada since even many Northerners would not help for fear of getting fined or arrested for breaking the law. Many Christians would say that Harriet should not have defied the government because of what it says in Romans 13 about obeying all those in authority over us (see Romans 13:1). That is a subject for another post in the future, but for now let us not judge her conscience. Slavery is evil and the Lord helped Harriet to rescue many people.

Harriet was able to discern the voice of the Lord speaking to her, warning her and giving her guidance. Because of this she was able to avoid capture many times. She said that she always knew when danger was near though she didn’t understand quite how exactly, but “pears like my heart go flutter, flutter,” and she would know that something bad was going to happen.

One example of this was a time when Harriet was going back north and she had a premonition that told her to turn aside and cross a stream. The stream was swollen in that place and she did not know how deep it was. She obeyed the whispered warning in her head and stepped in to cross the water. The men that were with her hung back, but when they saw that the water was only up to her chin, they followed her and all of them safely crossed the stream. Later they found out that there was a party waiting down the road to arrest her and if she hadn’t crossed the stream she would not have escaped.

Another time Harriet fell asleep in a park beneath a notice that was offering a reward for her capture! Of course, Harriet couldn’t read and had no idea of the irony until some friends found her and told her.

Because she was on the run, Harriet slept in wet swamps or in potato fields where she could lie hidden. Besides the obvious risk to her health there was always danger of being spotted. But the Lord always rescued her, sometimes through friends or by her own wits. And Harriet always gave the credit to God. When someone would express surprise at her boldness and daring she would reply, “Don’t I tell you, Missus, ’twasn’t me, ’twas de Lord!”

All through the War Between the States Harriet rescued slaves and nursed wounded soldiers. She was never paid for her efforts. Harriet remained poor for the rest of her life but she never complained.

Harriet died on March 10, 1913, in Auburn, New York at around the age of ninety-three! All through her life she had depended on the Lord and God had never disappointed her trust in Him.

Her life is an example of what can be done, even in the most horrible of circumstances, when a person does not give up or give in. Harriet’s attitude in life made all the difference in the world. Here we sit in our comfort and can’t seem to find time to help those around us. Harriet accomplished much in spite of illness, threats, poverty, and danger all around her. Her childlike faith and determination are an example for us all.